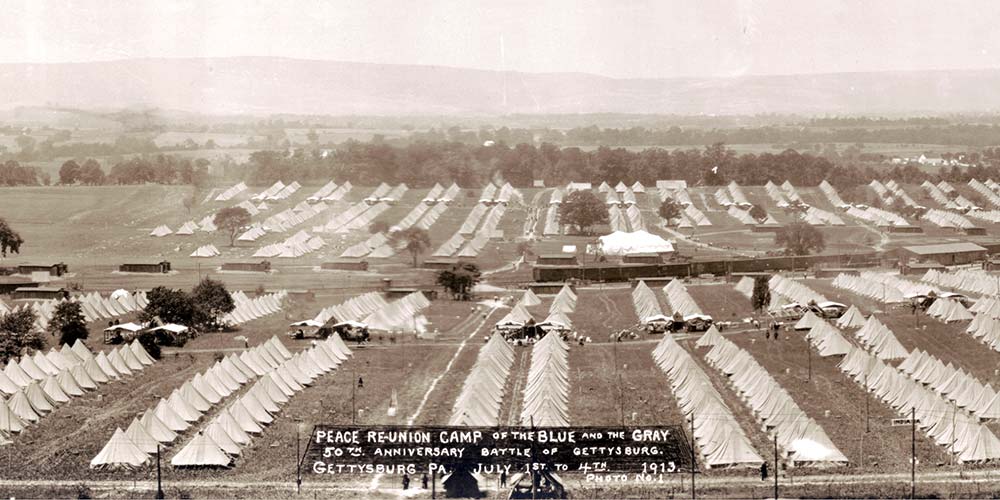

At the end of June in 1913 more than 53,000 veterans of the great battle, from both North and South, with an average age of 72—many now grizzled old men—arrived in Gettysburg for a federally-supported reunion of the Blue and Gray. The crowd included Union Major Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, at 93 the last surviving corps commander on either side, and perhaps the most notorious.

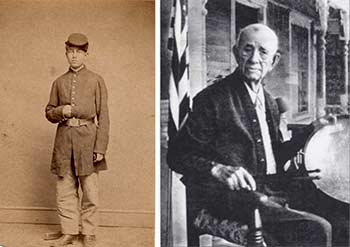

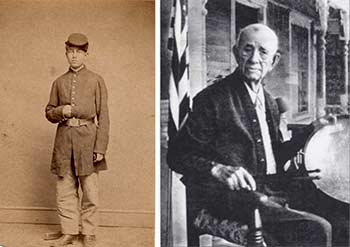

James Marion Lurvey, the last veteran of the Battle of Gettysburg.

It was reported that some of the veterans sought out the men who may have shot at them during the battle, in order to exchange military badges. Two men were said to have purchased a hatchet at a local hardware store, walked together to the site where their regiments fought, dug a hole there, and buried it. Within the vast encampment (see VR, above), events were held July 1-4 in a massive tent, filled with 13,000 chairs. On Independence Day President Woodrow Wilson addressed the crowd. Ironically, his administration had mandated segregation in the federal workforce just a few months earlier.

By the time of the 1913 reunion, the many venues of the Gettysburg Cyclorama—genuine and buckeye—had evoked a vivid emotional response from veterans of both armies. At a reunion of Confederate veterans in Birmingham, Alabama a few years earlier, one officer noted:

“I saw two [Confederate] veterans watching the Cyclorama of Gettysburg, and the tears streamed down their faces as they pointed out each spot that they had known, the locality of their command, the very trees where ‘Bill’ and ‘John’ and ‘Jim’ had fallen. That is the reason we come together to remind ourselves of the times that we spent together in the defense of our country.”

As Civil War historian David W. Blight wrote in 2002, “the lifeblood of reunion was the mutuality of soldiers’ sacrifice in a land where the rhetoric and reality of emancipation and racial equality occupied only the margins of history.”

It is likely that some of the veterans at the reunion in 1913 took the opportunity to visit the newly-restored Gettysburg Cyclorama, perhaps walking around the massive painting with the goal of identifying their own regiments, and pointing out to their comrades-in-arms the spots where they were standing on that fateful day in July 50 years earlier.

Since that reunion, the Cyclorama has undergone a number of restoration attempts, with some of the earlier ones creating more problems than they solved. The painting has been housed at Gettysburg in three different structures, one designed by the renowned architect Richard Neutra, and completed in 1962, only to be demolished in 2013 after attitudes about the preservation of the battlefield landscape changed. In the modern era, on an average July day, some two thousand visitors will marvel at the painting in its latest home, the visitors center which opened in 2008. These visitors will likely enter the Cyclorama auditorium before or after taking a tour of the battlefield, now so tranquil and park-like. As the lights dim, they will find themselves immersed into a very different environment: the painting’s vivid depiction of the chaos of war, a landscape of fire, smoke, and blood.

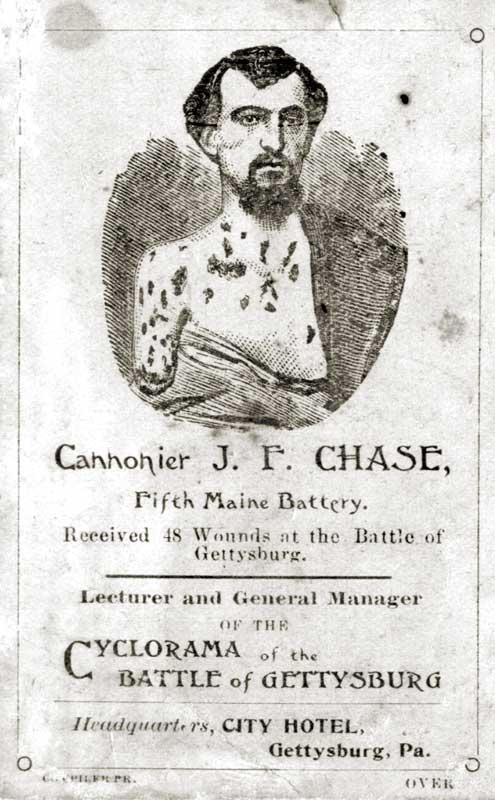

In 1886, J.F. Chase, a veteran who lost an arm and an eye at Gettysburg and won the Congressional Medal of Honor for his service at Chancellorsville, worked as the manager and lecturer for the New York version of the Cyclorama (see his later business card at the top of the page). Today, of course, there are no Gettysburg veterans alive to offer their first-person insights for visitors. But the Cyclorama now features a recorded narration, complete with a musical score, as well as sound and lighting effects, adding new dimensions of verisimilitude to the experience. Click here to view an excerpt.