Following the financial success of the four Battle of Gettysburg Cycloramas, entrepreneurs recruited painters over the next decade to create some three dozen other Civil War battles as cyclorama paintings. Shiloh, Second Bull Run, Vicksburg, Lookout Mountain, and Atlanta were just a few of the battles depicted. Some were tweaked to make them more appealing to Southern audiences. Paul Atkinson, the promoter who brought The Battle of Atlanta Cyclorama to that city, had a group of Confederate prisoners in the painting transformed into captive Yankees. More recently, however, the alterations pandering to southern audiences were removed.

In 1890, when Thomas Alva Edison invented the Kinetograph, the world’s first motion-picture camera, the writing was on the wall. By the mid-1890s the Battle of Gettysburg Cyclorama attractions in major cities were no longer financially viable. The four Philippoteaux canvases, once housed in majestic brick rotundas in some of America’s major cities, joined the “buckeyes” as attractions at regional fairs and other temporary venues.

The cyclorama building in Chicago was recycled for use as an armory, a boxing arena, a vaudeville theater, and a temple before it was demolished in 1921. The painting made the rounds of small towns and state fairs around the country, apparently coming to its inglorious end at a fair in Sioux City. A story in the Omaha World Herald (11/10/1894) headlined “A Great Picture Destroyed,” explains how the roof of the structure housing the cyclorama collapsed during a “heavy windstorm,” and how the painting was torn by the wind and soaked by the rain, which then froze solid. “The picture is most irreparably damaged,” the article concluded.

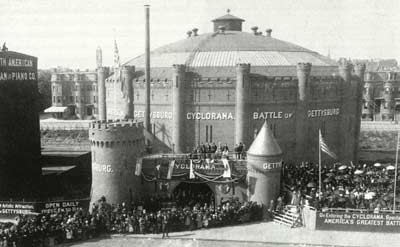

Cyclorama rotundas in Chicago, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn.

The Brooklyn cyclorama building only served for a year after its 1886 opening. The painting was not damaged when, during a March 1887 windstorm, parts of the chimney from an adjacent building fell onto the roof of the rotunda, broke through, and landed on one of the dead soldier mannequins of the diorama. The structure was knocked down after the painting was moved to a newly built Manhattan rotunda in August of 1887. Later, during its travels to smaller venues, the New York painting made an appearance at an 1894 gathering of Union veterans in Gettysburg. Ultimately the canvas was cut into pieces, some of which were distributed for display at GAR posts around the country.

The Philadelphia rotunda was converted in 1892 into the “Winter Circus,” featuring one ring circuses, boxing matches, and ballet, among other entertainments, including “burlesque football.” It was demolished around 1904 to make way for the Lyric Theatre. The Philadelphia painting was destroyed in a fire while on display in Niagara Falls in 1894.

Boston rotunda used as bicycle riding school (1890s).

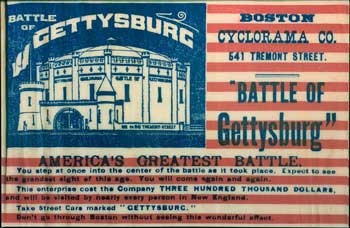

The Boston cyclorama rotunda—where the painting now in Gettysburg was first displayed in 1884—removed the battle canvas at the end of 1890. The venue then exhibited other cycloramas, starting with “Jerusalem on the Day of the Crucifixion.” After public tastes shifted away from cycloramas, the rotunda was used for roller skating, a carousel, rough riding displays, and a school teaching the new sport of bicycle riding. In April 1894, the last of the bare-fisted heavyweight boxers, John L. Sullivan, headlined a match in the rotunda.

The New England Electric Vehicle Company took over the structure from 1899 to 1901. In 1904, when the building was turned into the Tremont Garage, its two entrance towers were removed and a squared-off extension was constructed along Tremont Street, which now mostly hides the rotunda from view, except from above. In 1906 French bicycle racer Albert Champion located his factory within the garage, where he developed the A.C. Spark Plug. In 1923 the building became the home of the Boston Flower Exchange, which added the present entrance and the central skylight, then the largest in the country. The Boston Cyclorama remained the center for the region’s wholesale floral business until 1970, when it became part of the newly formed Boston Center for the Arts. The building was recognized as a Nationally Registered Historic Place in 1974. The rotunda today is available for hosting public or private events.

In the six-node VR environment below, you can virtually explore the Boston Cyclorama rotunda as it appears today, with its overhead lighting grid designed by Buckminster Fuller. To create this work, we were fortunate to have the cooperation of the Boston Center for the Arts, and Boston photographer Craig Bailey, who allowed us to use his elevated view of the building as the initial VR node.