The “Bloody Angle,” by William H. Tipton

The most intense fighting, including hand-to-hand combat, occurred at a spot by a low stone wall known as the “Angle.” For a brief moment, troops under the command of Confederate Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Armistead managed to breach the line before being repulsed when Union reinforcements rushed in. This spot is known as the “high-water mark of the Confederacy.” Armistead, leading the charge with his hat carried aloft on the tip of his sabre, was shot three times. The wounded general was captured by Union troops and died two days later in a field hospital. This moment, the focus of the Cyclorama, was clearly the turning point of the Battle of Gettysburg. Afterwards, many historians saw it as the turning point of the entire Civil War.

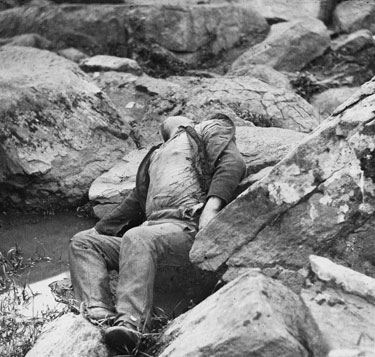

The opposing armies together suffered between 46,000 and 51,000 casualties—about a third of all the troops fighting at Gettysburg. Nearly 8,000 soldiers lost their lives. When Gen. Pickett was asked, years later, why his assault had failed, he said, “I’ve always thought the Yankees had something to do with it.”

As the Cyclorama’s Boston souvenir program put it:

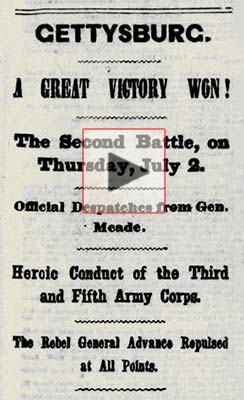

The tidings of the victory at Gettysburg came to the Northern people on the 4th of July, side by side with the tidings of the fall of Vicksburg. The proud old anniversary had perhaps never before been celebrated by the American people with hearts so thankful and so glad.

For the Union the victory at Gettysburg was a shot in the arm, a jubilant reversal from earlier drubbings at Chancellorsville and the Second Battle of Winchester. There was a palpable shift of momentum and cause for celebration in the streets of the cities of the Northeast. There would never be another strategic offensive by Lee’s army.

Four and a half months after the battle, at a time when the bleached bones of the fallen were still being discovered on the battlefield, President Abraham Lincoln arrived at Gettysburg to deliver his brief remarks, now so revered, at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery.