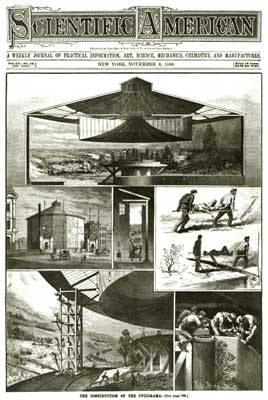

The first cyclorama shown in America was The Siege of Paris, exhibited in Philadelphia in 1876, before moving to others cities nationwide. But, it was to be the Civil War which would come to inspire most of the cycloramas that were later created and exhibited in America; and, it was the astounding commercial and artistic triumph of the Battle of Gettysburg Cyclorama that would be their inspiration.

The French creators of The Siege of Paris were the father and son team of Henri Felix and Paul Dominique Philippoteaux. Their cyclorama was a critical and financial success; the painting was shown from 1876 through 1888 in cities from coast to coast. Paul Philippoteaux was well known also from his work as the illustrator of adventure novels. His fame inspired Chicago entrepreneur Charles Willoughby to approach the artist with a business proposal. In 1881 he offered $50,000 (about $1,300,000 in 2021) to Paul Philippoteaux to create for Chicago what would become the first American-themed cyclorama. He wanted the artist to capture on the giant canvas the climatic Gettysburg battle of Pickett’s Charge.

The painter took up the challenge and later joined with Willoughby as one of the investors in the National Panorama Company and other enterprises to finance the completion of four (nearly identical) paintings and the construction of the cyclorama buildings to house them in Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, and New York.

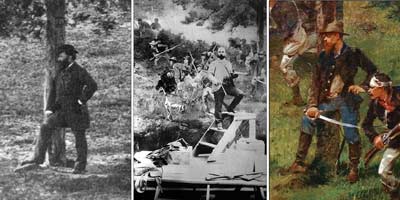

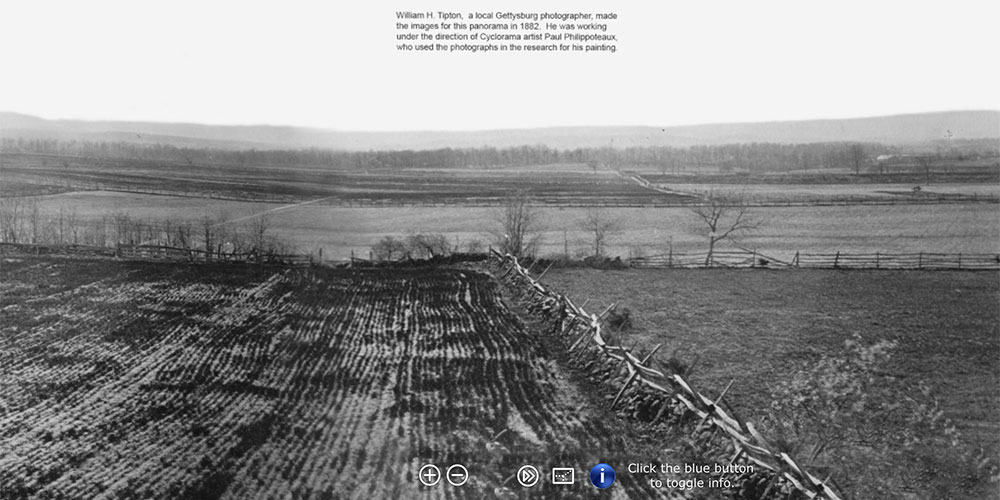

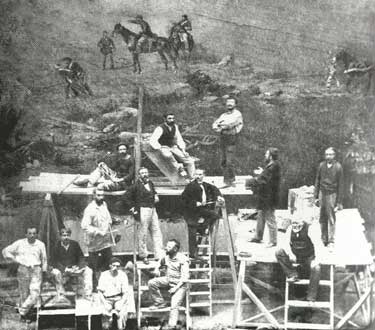

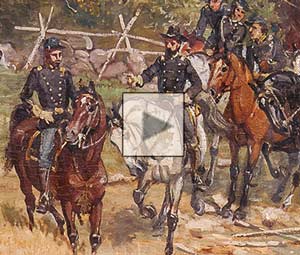

Philippoteaux (see portraits, right) soon began his extensive research in earnest, intending to make his painting as historically accurate as possible. In May of 1882, while in New York City, the artist visited with Union Generals Winfield Hancock, Alexander Webb, and Abner Doubleday. These generals may be seen together here in the Cyclorama. By engaging these officers and other veterans in his planning, Philippoteaux worked to ensure that his painting would withstand the intense scrutiny it would receive from those who were, two decades earlier, the actors in the bloody drama to be portrayed on his canvas.

It should be noted, however, that while Philippoteaux selected a historical event—Pickett’s Charge and its “high-water mark of the Confederacy”—he did take some artistic license. The work is allegorical, and thus some of the incidents depicted in the painting happened just before, or just after, the high-water mark’s moment in time. The Gettysburg Cyclorama book’s authors suggested that “about 15 minutes of action was compressed into one ‘snapshot’ that became the painting.”