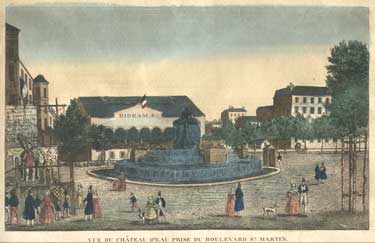

A cyclorama is a large circular environment, usually a specially-constructed polygonal building, with a central rotunda, designed to display a very large panoramic painting depicting a 360° scene on the interior walls. The painting typically could be about 50 feet high and 400 feet in circumference, its canvas weighing up to 10 tons. The audience would view the painting from a raised platform in the center of the building. As the art form evolved, installations usually incorporated a diorama, a theatrical landscape extending out from the painting and filling the space between the painting and the viewing platform.

This would extend some features of the painting directly into the corresponding physical objects of the diorama, helping to complete the illusion. For one example, note how the painted well and bucket in the Gettysburg Cyclorama are integrated with the objects of its diorama (photo at left).

According to the authors of The Gettysburg Cyclorama, “By blurring all boundaries between the real and created worlds through the use of the circular canvas, diorama, and canopy, the viewers experienced a sense of immersion as they stepped from dimly lit stairs into the center of the realistic scene.”

In 1787, Robert Barker, a painter in Edinburgh, Scotland, wished to capture the view from the city’s Calton Hill. He created a 360° painting of the subject, and coined the word “panorama” to describe his work. In 1792 it was shown in London in a tailor-made circular theatre—the world’s first cyclorama building. A similar early cyclorama in Switzerland, the oldest one (1814) that survives, may be seen here.