Paul Philippoteaux began his work on the Battle of Gettysburg Cyclorama in 1881, the last year of the Rutherford B. Hayes administration. President Hayes had been edged into the White House by a single electoral vote thanks to the Compromise of 1877, a devil’s bargain in which the Republican president agreed to effectively end Reconstruction by withdrawing federal troops from the states of the former Confederacy. As Yale historian Timothy Snyder wrote in 2021, the Compromise marked “…the beginning of segregation, legal discrimination and Jim Crow. It is the original sin of American history in the post-slavery era, our closest brush with fascism so far.”

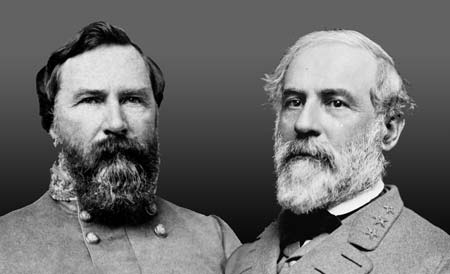

The Compromise of 1877 no doubt encouraged post-war white supremacy, which the country is still grappling with today. However, the undoing of what was won by the bloody sacrifices of the Civil War had begun more than a decade earlier. The hard-fought freedoms gained not only by the Union army, but also by more than a century of struggle by abolitionists and freedom fighters began to erode just 15 days after the surrender of Gen. Robert E. Lee. On April 14, 1865 President Lincoln was assassinated and Vice President Andrew Johnson was suddenly elevated to the White House.

Johnson, a Democrat from Tennessee, kept nine persons of his household enslaved until a month after the Battle of Gettysburg. As president, Johnson moved for the rapid restoration to the Union of the renegade southern states, without putting in place any effective protection for the liberated Black people who had been long held in bondage. He also reneged on the “forty acres and a mule” promised earlier to some of those newly freed and returned all the seized plantation lands to their former owners. Black Americans, whose lives in brutal chattel servitude provided the financial foundation of the antebellum South, were forced by their limited opportunities to continue their economic role post-Reconstruction as sharecroppers.

Furthermore, targeted penal codes served to continue the economic enslavement in another form; in 1898 Alabama, 73% of the state’s revenue came from renting out the forced labor of Black Americans.

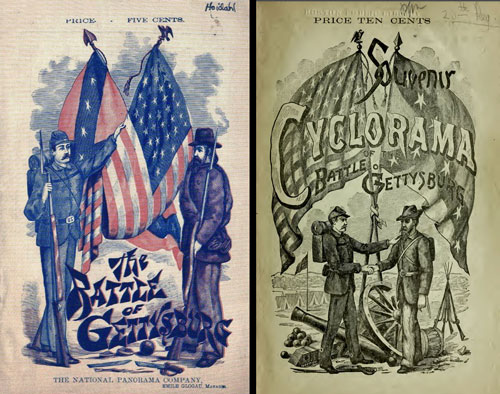

With this historical context, we can imagine how this tragic turn of events might explain why a wounded President Lincoln was metaphorically depicted here in the Cyclorama, being carried off the field of battle. However, with that possible—but improbable—exception, the Cyclorama contains no visual reference as to why the battle was fought. Devoid of any reference to slavery, the major cause of the war, what then was the significance of the painting?